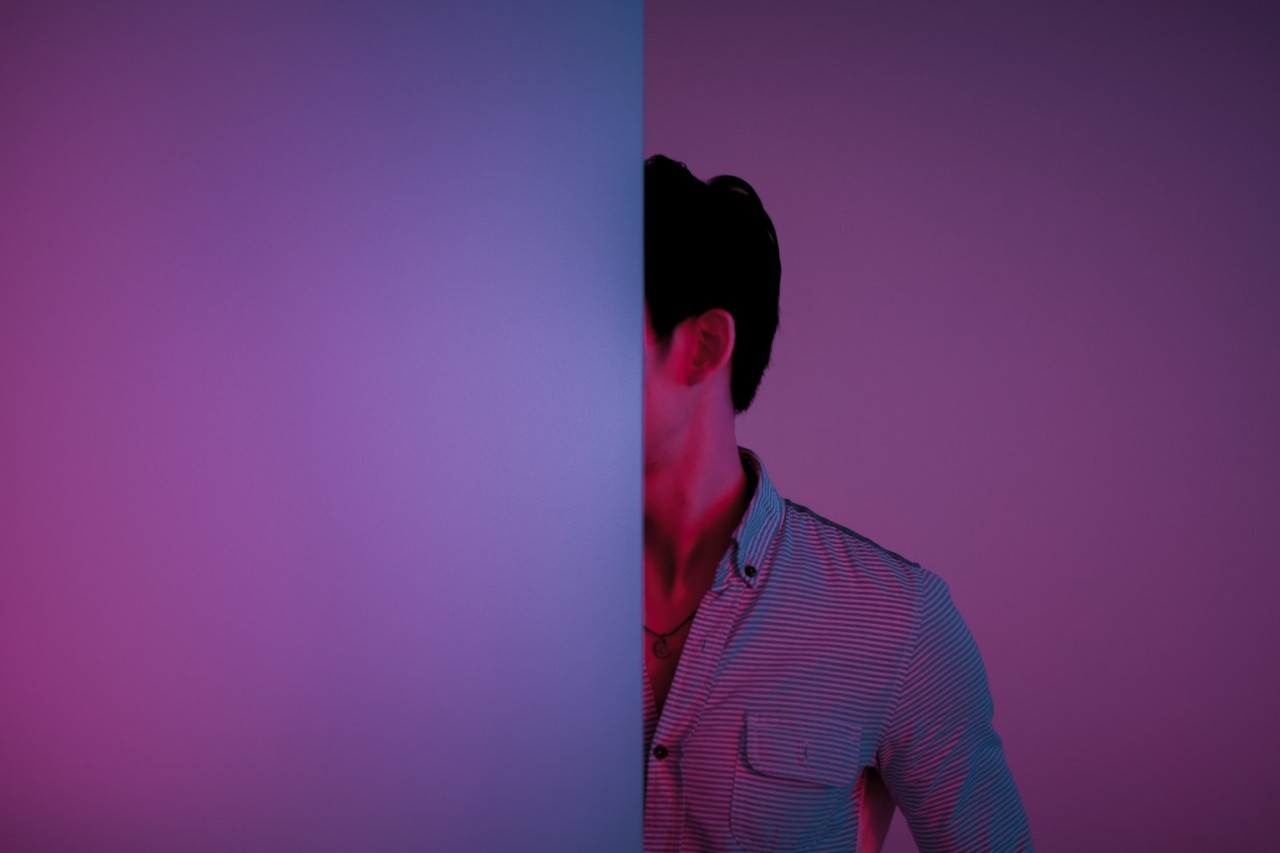

Artists are people driven by the tension between the desire to communicate and the desire to hide. (Donald Woods Winnicott)

The above quotation describes a dynamic I know well. Publishing a new blog post every Wednesday means each week I need to identify a topic and then write a piece I’m happy to present to the world. Some are more personal than others, but whatever the topic there’s a balance to be struck between wanting to communicate and respecting my vulnerability.

The Desire to Communicate

As I’ve written previously, I can’t imagine a time when I’m not expressing myself creatively in some way. That’s taken many different forms over the years, including clay modeling, painting, woodwork, and photography. Mostly, though, I’ve sought to communicate through my writing. These days that’s primarily through this blog, but in the past it’s included poetry, factual articles, short stories, and books.

Friends have described me as having a passion for writing, or it being my purpose in life. Neither feels right to me. I do spend a considerable amount of time writing, one way or another. Apart from blogging, this includes personal correspondence, chatting online with friends, and the diary I’ve written ever day since I was fourteen years old. For all that, it’s not something I enjoy.

The book Fran and I wrote took four years of almost constant work, from original idea to publication. I don’t regret it. I’m immensely proud and consider it one of my greatest achievements in any field. But it wasn’t an easy road for either of us and there were times we came close to setting it aside. Blogging is no less demanding of my time, energy, and focus. There’s a sense of achievement when I complete a post, but my publishing schedule means there’s little time to appreciate my success before pressing on with the next article.

Why do it then? From my perspective, writing isn’t something I choose to do at all. It’s more like a need or compulsion that’s been a part of my life — a part of me — since my teens. If I try and rationalise it, I can identify three reasons for writing.

- To explore my situation and experience

- To share and educate

- To invite input from others

Most fundamentally, writing is how I process and explore what’s going on for me. That’s especially true of my journal, but applies more generally. This blog post is a good example. It’s giving me the opportunity to examine what writing means to me, and my creative boundaries. I keep a “scrapbook” document within easy reach on my phone. I use this to capture ideas, notes, and thoughts whenever they occur to me. Some may be further expanded in my journal or blog posts, but many go no further. They exist as an informal appendix to my life, and I review them regularly for the insights and ideas they contain.

Sharing and educating were the motivations behind the book Fran and I wrote together. Recognising there was little material available for anyone wanting to help and support a friend who lives with mental illness, we wrote High Tide, Low Tide: The Caring Friend’s Guide to Bipolar Disorder to share what we’d learned through our own mutually supportive friendship. That same desire to share and educate underlies the content we publish on our blog and elsewhere.

Communicating isn’t all one way, of course. Whether it’s through our book or blog, social media, or private conversations, one of the key aspects of writing for me is receiving feedback and input from other people. We get fewer blog comments than I’d like, but those we do receive are incredibly valuable. For the same reason, we love having guest bloggers. If you’d like to guest here, check out our contact page for guidelines. Many of our posts include ideas and insights from other people. One recent example explored sympathy, empathy, and compassion and featured contributions from people who responded to my invitation on social media.

But these positive aspects don’t tell the whole story. In and of themselves, they’re probably not enough to keep me writing. If I’m honest, I write because I’m scared to stop. It often feels to me as though writing is the only thing I have that has any real meaning, value, or purpose. If I stopped writing, what would be left? At different times, I’ve thought about stopping my personal journal. I’ve certainly considered giving up blogging, or at least taking a break from it. In both cases, the very routine — daily journal entries and weekly blog posts — imposes an imperative to continue. Were I to interrupt either, I’d find it very difficult to pick up again at some later date. And so I continue, as much from fear as anything else.

The Desire to Hide

There can be many reasons for hiding, which in this context I’ll define as choosing not to communicate about something. We may feel inadequate to the task because we lack the skills or the experience to do so effectively. This is the reason I choose not to write about certain things, as I described in a post about blogging honestly.

There are topics I’d like to write about but haven’t yet found a way to approach them as I’d wish to. These include my perspective as a caring friend when someone I know has taken an overdose or harmed themself. I can’t imagine ever writing about abuse, addiction, rape, or trauma. Those are too far beyond my lived experience for me to do them justice.

It’s wise to be aware of our limitations, but it’s easy to become stuck in a mindset that keeps us from trying new things or exploring beyond the boundaries of our comfort zone. Those boundaries may still be relevant and useful, but it’s possible we’ve outgrown them. It’s worth checking in with the stories we tell ourselves, especially those that begin “I’m not the kind of person who ...” Maybe we are or could be, if we gave ourself permission to try.

I’ve written about things I’d once have felt uncomfortable sharing. These include open letters to my mother and to my father, and how I let a friend down when she was most in need. In recent years I’ve written about my physical and mental health for the first time, in such articles as My First Doctor’s Appointment in 30 Years, My Visit to Grey St. Opticians, Anxiety and Me, Return to Down, and This Boy Gets Sad Too. I explored what being a man means to me for International Men’s Day last year, and have described my self-doubt and feeling a fraud. This blog post is something I couldn’t have imagined writing in the past. It’s an example of how I feel increasingly comfortable being open and honest about myself.

That said, there are areas where I still feel the need to hide. For right or wrong, most of the reasons are fear-based. As I’ve previously described:

I would like to be completely honest, open, and genuine in everything I do and write, but honesty means admitting I’m afraid people might not like what I’ve shared, and won’t like me as a result. Who I am — who I really am, with my insights, experience, and wisdom; but also my faults, failings, and hang-ups — is all I have to offer. There are things I’ve chosen not to write about because of that fear.

I’m wary of discussing topics where I’ve not reached a clear decision or opinion, or where I feel unable to justify my position logically or respond adequately to the counter arguments. For these reasons amongst others, I choose not to write publically about religion, politics, gender issues, or war and conflict. With a few exceptions, I don’t write about my personal relationships, present or past. I don’t discuss sex, things I’m ashamed of or embarrassed about, or things entrusted to me by others. What are my fears, exactly? Several spring to mind.

- Fear of embarrassment

- Fear of ridicule, censure, or criticism

- Fear of negative or hurtful repercussions

- Fear of upsetting or disappointing people

- Fear of inciting controversy or anger

How realistic are these fears? That’s difficult to gauge in advance, which is why the urge to hide can be so debilitating. I mentioned there were times Fran and I came close to setting our book aside. That wasn’t because of the effort involved, although that brought its own challenges. It was because Fran feared the negative repercussions of revealing so much about herself, especially her mental health. She had good reason to be cautious, having experienced a great deal of stigma and discrimination in the past. Her health and wellbeing were always my primary concern. On several occasions we came close to setting the entire thing aside. It’s a testament to Fran’s courage that we completed the project.

I had no such fears, but the situation was very different for me. I was mostly sharing caring and supportive aspects of myself which were unlikely to attract negative attention. The closest thing to criticism directed at me was a sense of incredulity that I could devote so much time and attention to someone outside my immediate family. I feel far less confident sharing other aspects of my life, personality, and behaviour. It’s scary to contemplate lifting the lid and exposing my inner self to the world. Hiding may be neither honest nor honourable, but it can be comfortable. Fear can also be healthy, in that it guards us against sharing too much or inappropriately. Maintaining healthy boundaries is important. We can be honest and genuine without sharing everything with everyone all the time.

You may have heard the injunction “write what scares you.” But why would you? Why would I? One reason is to help other people take an equivalent step. So much of what I’ve learned about mental illness is the result of reading, watching, and listening to people willing to share what it’s like for them. It’s one of the very best ways to educate yourself about your loved one’s mental health condition, or indeed your own. There are other benefits too. We grow by being open about ourselves. That doesn’t have to mean sharing publically, but however we do it, choosing to communicate rather than hide is an act of commitment to who we are. Knowing that something we’ve said or shared has helped someone is profoundly encouraging and validating. In simple terms, helping people helps you too.

But what about the dark bits? I was discussing some of my past writing with a friend recently. Specifically, the short stories written between 1996 and 2005 when I ran a Tolkien fan group called Middle-earth Reunion. I’m proud of many of those tales. I referenced a few in We Are All Made of Stories, in which I discussed storytelling as a vehicle for self-exploration. My friend asked if any of the characters in my stories represented me. Aside from a few tales in which I appear as myself — including this one — there are only two characters I identify with to any great extent. The first is Malcolm, the confused and largely inadequate antihero of “Playing at Darkness.” The second is dour widower William (Bill) Stokes in “And Men Myrtles.”

It’s neither easy not straightforward for me to admit this. I’m fond of Malcolm and Bill, and the stories in which they appear represent the best fiction I’ve ever written. Nevertheless, there are aspects of their personalities and behaviour that I strongly disavow. In these and other tales there are instances of sexism, classism, obsession, inappropriate behaviour, and aggression. Some of these are fundamental to the narrative, others arguably less so. They sit uneasily with me now precisely because I recognise echoes in my own nature, behaviour, and experience in the past.

These stories were written almost twenty years ago. It would be convenient to say that’s where I was at the time, but I’ve learned and moved on. In many cases I believe that to be true, but the fact they make uneasy reading today suggests not all of the work has been done. I may or may not make these pieces public, but these are important topics in their own right. I do no one any good, myself included, by hiding them away or hiding from them.

I’ll close with two quotations by therapist and coach Saadia Z. Yunus. The first speaks to the fear of wanting to speak our truth.

Your heart may race every time you’re about to speak up for yourself. This doesn’t mean it is wrong. It means it didn’t feel safe when you spoke up in the past. Have grace for yourself, breathe through it and speak. Your voice deserves to be heard.

I’m reminded of something I wrote myself, years ago: “Speak your truth. Whisper it. Scream it. You never know who might need to hear what only you can say. This stuff matters. You matter.” The second quotation by Saadia Z. Yunus asks a very important question.

When did you receive the message that everyone around you has to be OK and comfortable at the expense of your own comfort, autonomy, and self?

We may, with good reason, fear the repercussions if by speaking out we upset other people. No one, however, has the right not to be upset or offended. Other people’s comfort is not more important than our commitment to the truth as we perceive it or our lives as we live them. On my bookshelf is a copy of Susan Jeffers’ Feel the Fear And Do It Anyway. I think it’s due for a re-read.

Photo by Road Trip with Raj at Unsplash.